- Home

- Nick Hornby

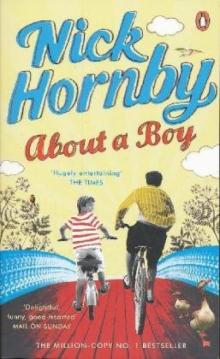

About a Boy

About a Boy Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

ABOUT A BOY

‘It is absolutely unthinkable that you will be able to finish even the

first chapter without seeing a little bit of yourself and everyone

you know in both Will and his newly “adopted” progeny Marcus’

Irish Independent

‘A touching tale that deserves to make every adult laugh out loud’

Mail on Sunday

‘Hornby’s sharp observations and his quirky comedic instincts ensure

that our journey is entertaining, funny – and occasionally affecting’

New York Times

‘The portrait of Marcus’s claustrophobic home life, his troubles at

school and general bewilderment at the behaviour of adults, is

written with great skill. Indeed with a sympathetic genius that more

self-conscious writers will envy’ Daily Mail

‘A logical extension of Hornby’s territory, combining the humour

and keen perception of his earlier books with a harsher set of

facts; a north London landscape slightly reminiscent of Joseph

Connolly and Martin Amis. The psychology of Hornby’s

characters is carefully, thoughtfully and gently done. There

is a heart to Hornby’s writing which sets its world apart from

those of Connolly or Amis’ Tobias Hill, Observer

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nick Hornby was born in 1957. He is the author of four novels, High Fidelity, About a Boy, How to be Good and a Long Way Down; three Works of non-fiction, Fever Pitch (winner of the William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award), 31 Songs (shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award), and The Polysyllabic Spree; and a Pocket Penguin book of short Stories, Otherwise Pandemonium. He has also edited two anthologies, My Favourite Year and Speaking with the Angel. In 1999 he was awarded the E. M. Forster Award by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2002 he won the W. H. Smith Award for Fiction, and in 2003 he was honoured with the Writers’ Writer Award at the Orange Word International Writers Festival. Nick Hornby lives and works in Highbury, North London.

NICK HORNBY

About a Boy

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi -110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

Published by Victor Gollancz 1998

Published in Penguin Books 2000

36

Copyright © Nick Hornby, 1998

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-141-92435-9

Love and thanks to David Evans,

Adrienne Maguire, Caroline Dawnay,

Virginia Bovell, Abigail Morris,

Wendy Carlton, Harry Ritchie and

Amanda Posey. Music provided by

Wood in Upper Street, London N1.

In memory of Liz Knights

one

‘Have you split up now?’

‘Are you being funny?’

People quite often thought Marcus was being funny when he wasn’t. He couldn’t understand it. Asking his mum whether she’d split up with Roger was a perfectly sensible question, he thought: they’d had a big row, then they’d gone off into the kitchen to talk quietly, and after a little while they’d come out looking serious, and Roger had come over to him, shaken his hand and wished him luck at his new school, and then he’d gone.

‘Why would I want to be funny?’

‘Well, what does it look like to you?’

‘It looks to me like you’ve split up. But I just wanted to make sure.’

‘We’ve split up.’

‘So he’s gone?’

‘Yes, Marcus, he’s gone.’

He didn’t think he’d ever get used to this business. He had quite liked Roger, and the three of them had been out a few times; now, apparently, he’d never see him again. He didn’t mind, but it was weird if you thought about it. He’d once shared a toilet with Roger, when they were both busting for a pee after a car journey. You’d think that if you’d peed with someone you ought to keep in touch with them somehow.

‘What about his pizza?’ They’d just ordered three pizzas when the argument started, and they hadn’t arrived yet.

‘We’ll share it. If we’re hungry.’

‘They’re big, though. And didn’t he order one with pepperoni on it?’ Marcus and his mother were vegetarians. Roger wasn’t.

‘We’ll throw it away, then,’ she said.

‘Or we could pick the pepperoni off. I don’t think they give you much of it anyway. It’s mostly cheese and tomato.’

‘Marcus, I’m not really thinking about the pizzas right now.’

‘OK. Sorry. Why did you split up?’

‘Oh… this and that. I don’t really know how to explain it.’

Marcus wasn’t surprised that she couldn’t explain what had happened. He’d heard more or less the whole argument, and he hadn’t understood a word of it; there seemed to be a piece missing somewhere. When Marcus and his mum argued, you could hear the important bits: too much, too expensive, too late, too young, bad for your teeth, the other channel, homework, fruit. But when his mum and her boyfriends argued, you could listen for hours and still miss the point, the thing, the fruit and homework part of it. It was like they’d been told to argue and just came out with anything they could think of.

‘Did he have another girlfriend?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Have you got another boyfriend?’

She laughed. ‘Who would that be? The guy who took the pizza orders? No, Marcus, I haven’t got another boyfriend. That’s not how it works. Not when you’re a thirty-eight-year-old working mother. There’s a time problem. Ha! There’s an everything problem. Why? Does it bother you?’

‘I dunno.’

And he didn’t know. His mum was sad, he knew that – she cried a lot now, more than she did before they moved to London – but he had no idea whether that was anything to do with boyfriends. He kind of hoped it was, because then it would all get sorted out. She would meet someone, and he would make her happy. Why not? His mum was pretty, he thought, and nice, and funny sometimes, and he reckoned there must be loads of blokes like Roger around. If it wasn’t boyfriends, though, he didn’t know what it could be, apart from something bad.

‘Do you mind me ha

ving boyfriends?’

‘No. Only Andrew.’

‘Well, yes, I know you didn’t like Andrew. But generally? You don’t mind the idea of it?’

‘No. Course not.’

‘You’ve been really good about everything. Considering you’ve had two different sorts of life.’

He understood what she meant. The first sort of life had ended four years ago, when he was eight and his mum and dad had split up; that was the normal, boring kind, with school and holidays and homework and weekend visits to grandparents. The second sort was messier, and there were more people and places in it: his mother’s boyfriends and his dad’s girlfriends; flats and houses; Cambridge and London. You wouldn’t believe that so much could change just because a relationship ended, but he wasn’t bothered. Sometimes he even thought he preferred the second sort of life to the first sort. More happened, and that had to be a good thing.

Apart from Roger, not much had happened in London yet. They’d only been here for a few weeks – they’d moved on the first day of the summer holidays – and so far it had been pretty boring. He had been to see two films with his mum, Home Alone 2, which wasn’t as good as Home Alone 1, and Honey, I Blew Up the Kid, which wasn’t as good as Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, and his mum had said that modern films were too commercial, and that when she was his age… something, he couldn’t remember what. And they’d been to have a look at his school, which was big and horrible, and wandered around their new neighbourhood, which was called Holloway, and had nice bits and ugly bits, and they’d had lots of talks about London, and the changes that were happening to them, and how they were all for the best, probably. But really they were sitting around waiting for their London lives to begin.

The pizzas arrived and they ate them straight out of the boxes.

‘They’re better than the ones we had in Cambridge, aren’t they?’ Marcus said cheerfully. It wasn’t true: it was the same pizza company, but in Cambridge the pizzas hadn’t had to travel so far, so they weren’t quite as soggy. It was just that he thought he ought to say something optimistic. ‘Shall we watch TV?’

‘If you want.’

He found the remote control down the back of the sofa and zapped through the channels. He didn’t want to watch any of the soaps, because soaps were full of trouble, and he was worried that the trouble in the soaps would remind his mum of the trouble she had in her own life. So they watched a nature programme about this sort of fish thing that lived right down the bottom of caves and couldn’t see anything, a fish that nobody could see the point of; he didn’t think that would remind his mum of anything much.

two

How cool was Will Freeman? This cool: he had slept with a woman he didn’t know very well in the last three months (five points). He had spent more than three hundred pounds on a jacket (five points). He had spent more than twenty pounds on a haircut (five points) (How was it possible to spend less than twenty pounds on a haircut in 1993?). He owned more than five hip-hop albums (five points). He had taken Ecstasy (five points), but in a club and not merely at home as a sociological exercise (five bonus points). He intended to vote Labour at the next general election (five points). He earned more than forty thousand pounds a year (five points), and he didn’t have to work very hard for it (five points, and he awarded himself an extra five points for not having to work at all for it). He had eaten in a restaurant that served polenta and shaved parmesan (five points). He had never used a flavoured condom (five points), he had sold his Bruce Springsteen albums (five points), and he had both grown a goatee (five points) and shaved it off again (five points). The bad news was that he hadn’t ever had sex with someone whose photo had appeared on the style page of a newspaper or magazine (minus two), and he did still think, if he was honest (and if Will had anything approaching an ethical belief, it was that lying about yourself in questionnaires was utterly wrong), that owning a fast car was likely to impress women (minus two). Even so, that gave him… sixty-six! He was, according to the questionnaire, sub-zero! He was dry ice! He was Frosty the Snowman! He would die of hypothermia!

Will didn’t know how seriously you were supposed to take these questionnaire things, but he couldn’t afford to think about it; being men’s-magazine cool was as close as he had ever come to an achievement, and moments like this were to be treasured. Sub-zero! You couldn’t get much cooler than sub-zero! He closed the magazine and put it on to a pile of similar magazines that he kept in the bathroom. He didn’t save them all, because he bought too many for that, but he wouldn’t be throwing this one out in a hurry.

Will wondered sometimes – not very often, because historical speculation wasn’t something he indulged in very often – how people like him would have survived sixty years ago. (‘People like him’ was, he knew, something of a specialized grouping; in fact, there couldn’t have been anyone like him sixty years ago, because sixty years ago no adult could have had a father who had made his money in quite the same way. So when he thought about people like him, he didn’t mean people exactly like him, he just meant people who didn’t really do anything all day, and didn’t want to do anything much, either.) Sixty years ago, all the things Will relied on to get him through the day simply didn’t exist: there was no daytime TV, there were no videos, there were no glossy magazines and therefore no questionnaires and, though there were probably record shops, the kind of music he listened to hadn’t even been invented yet. (Right now he was listening to Nirvana and Snoop Doggy Dogg, and you couldn’t have found too much that sounded like them in 1933.) Which would have left books. Books! He would have had to get a job, almost definitely, because he would have gone round the twist otherwise.

Now, though, it was easy. There was almost too much to do. You didn’t have to have a life of your own any more; you could just peek over the fence at other people’s lives, as lived in newspapers and EastEnders and films and exquisitely sad jazz or tough rap songs. The twenty-year-old Will would have been surprised and perhaps disappointed to learn that he would reach the age of thirty-six without finding a life for himself, but the thirty-six-year-old Will wasn’t particularly unhappy about it; there was less clutter this way.

Clutter! Will’s friend John’s house was full of it. John and Christine had two children – the second had been born the previous week, and Will had been summoned to look at it – and their place was, Will couldn’t help thinking, a disgrace. Pieces of brightly coloured plastic were strewn all over the floor, videotapes lay out of their cases near the TV set, the white throw over the sofa looked as if it had been used as a piece of gigantic toilet paper, although Will preferred to think that the stains were chocolate… How could people live like this?

Christine came in holding the new baby while John was in the kitchen making him a cup of tea. ‘This is Imogen,’ she said.

‘Oh,’ said Will. ‘Right.’ What was he supposed to say next? He knew there was something, but he couldn’t for the life of him remember what it was. ‘She’s…’ No. It had gone. He concentrated his conversational efforts on Christine. ‘How are you, anyway, Chris?’

‘Oh, you know. A bit washed out.’

‘Been burning the candle at both ends?’

‘No. Just had a baby.’

‘Oh. Right.’ Everything came back to the sodding baby. ‘That would make you pretty tired, I guess.’ He’d deliberately waited a week so that he wouldn’t have to talk about this sort of thing, but it hadn’t done him any good. They were talking about it anyway.

John came in with a tray and three mugs of tea.

‘Barney’s gone to his grandma’s today,’ he said, for no reason at all that Will could see.

‘How is Barney?’ Barney was two, that was how Barney was, and therefore of no interest to anyone apart from his parents, but, again, for reasons he would never fathom, some comment seemed to be required of him.

‘He’s fine, thanks,’ said John. ‘He’s a right little devil at the moment, mind you, and he’s not too sure what to make of Imogen, but…

he’s lovely.’

Will had met Barney before, and knew for a fact he wasn’t lovely, so he chose to ignore the non sequitur.

‘What about you, anyway, Will?’

‘I’m fine, thanks.’

‘Any desire for a family of your own yet?’

I would rather eat one of Barney’s dirty nappies, he thought. ‘Not yet,’ he said.

‘You are a worry to us,’ said Christine.

‘I’m OK as I am, thanks.’

‘Maybe,’ said Christine smugly. These two were beginning to make him feel physically ill. It was bad enough that they had children in the first place; why did they wish to compound the original error by encouraging their friends to do the same? For some years now Will had been convinced that it was possible to get through life without having to make yourself unhappy in the way that John and Christine were making themselves unhappy (and he was sure they were unhappy, even if they had achieved some peculiar, brain-washed state that prevented them from recognizing their own unhappiness). You needed money, sure – the only reason for having children, as far as Will could see, was so they could look after you when you were old and useless and skint – but he had money, which meant that he could avoid the clutter and the toilet-paper throws and the pathetic need to convince friends that they should be as miserable as you are.

John and Christine used to be OK, really. When Will had been going out with Jessica, the four of them used to go clubbing a couple of times a week. Jessica and Will split up when Jessica wanted to exchange the froth and frivolity for something more solid; Will had missed her, temporarily, but he would have missed the clubbing more. (He still saw her, sometimes, for a lunchtime pizza, and she would show him pictures of her children, and tell him he was wasting his life, and he didn’t know what it was like, and he would tell her how lucky he was he didn’t know what it was like, and she would tell him he couldn’t handle it anyway, and he would tell her he had no intention of finding out one way or the other; then they would sit in silence and glare at each other.) Now John and Christine had taken the Jessica route to oblivion, he had no use for them whatsoever. He didn’t want to meet Imogen, or know how Barney was, and he didn’t want to hear about Christine’s tiredness, and there wasn’t anything else to them any more. He wouldn’t be bothering with them again.

Funny Girl

Funny Girl 31 Songs

31 Songs Fever Pitch

Fever Pitch Not a Star and Otherwise Pandemonium

Not a Star and Otherwise Pandemonium The Complete Polysyllabic Spree

The Complete Polysyllabic Spree Songbook

Songbook An Education

An Education Slam

Slam High Fidelity

High Fidelity Speaking With the Angel

Speaking With the Angel How to Be Good

How to Be Good Stuff I've Been Reading

Stuff I've Been Reading About a Boy

About a Boy A Long Way Down

A Long Way Down Juliet, Naked

Juliet, Naked State of the Union

State of the Union Ten Years in the Tub: A Decade Soaking in Great Books

Ten Years in the Tub: A Decade Soaking in Great Books Books, Movies, Rhythm, Blues: Twenty Years of Writing About Film, Music and Books

Books, Movies, Rhythm, Blues: Twenty Years of Writing About Film, Music and Books Just Like You

Just Like You More Baths Less Talking

More Baths Less Talking Books, Movies, Rhythm, Blues

Books, Movies, Rhythm, Blues